It’s called Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) and can remove PFAS “forever chemicals” at record speed; 100x faster than activated carbon. It sounds like a revolution, but you can’t buy one just yet. Here’s what the science actually says, why reverse osmosis still wins for now, and when LDH filters might finally make it to your tap.

By now, you’ve likely heard about PFAS; the “forever chemicals” lurking in tap water across the country. The bad news: they don’t break down on their own. The good news: scientists keep getting better at pulling them out. And the latest breakthrough in PFAS removal is turning heads in a big way.

You might find these posts helpful:

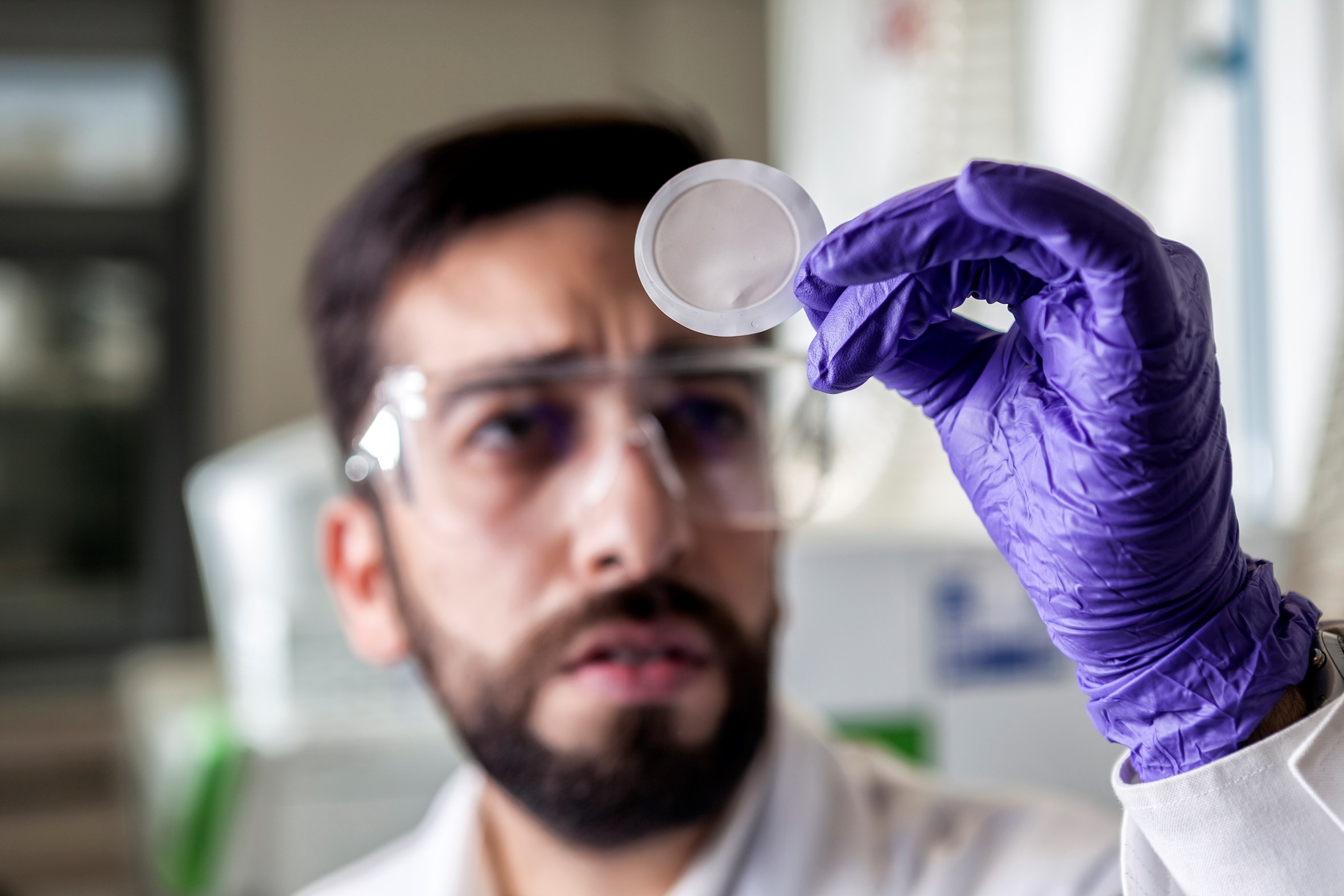

Researchers at Rice University unveiled a new breakthrough in late 2025 that can remove PFAS from water in literal minutes, something that was basically unheard of before. The material is called a Layered Double Hydroxide, or LDH, and the results from lab testing are kind of staggering. But before you go hunting for an LDH water filter on Amazon, there’s a lot to understand about what this technology can and can’t do right now.

We dug into the peer-reviewed research, compared it against what we know about reverse osmosis (the current gold standard for home PFAS removal), and broke down exactly where things stand. Spoiler: it’s complicated, but very promising!

What Is a Layered Double Hydroxide Water Filter?

If you’re not a chemist, the name Layered Double Hydroxide might sound like something from a graduate thesis. And, well, it kind of is. But the core concept is surprisingly intuitive once you understand what PFAS actually are.

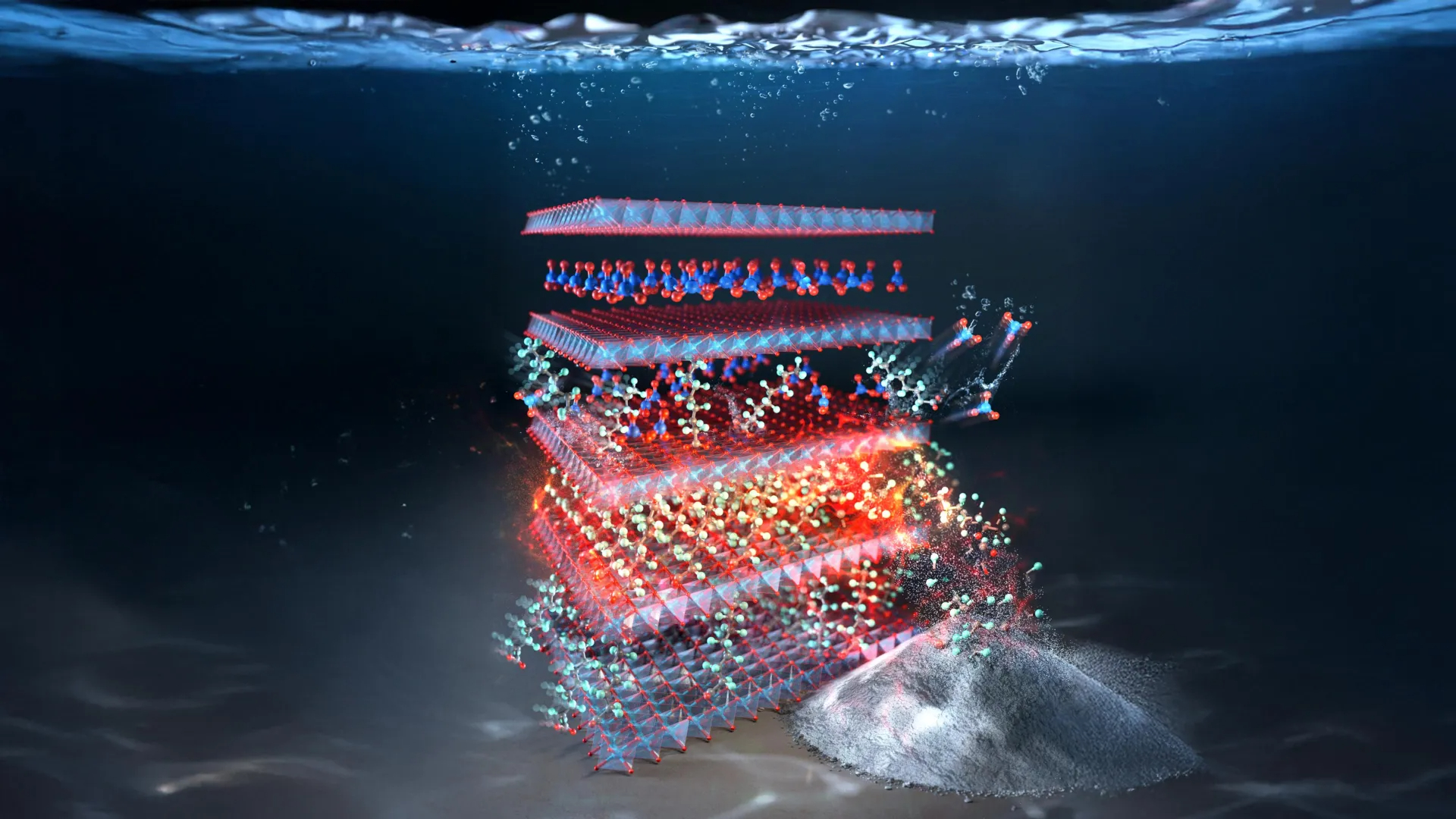

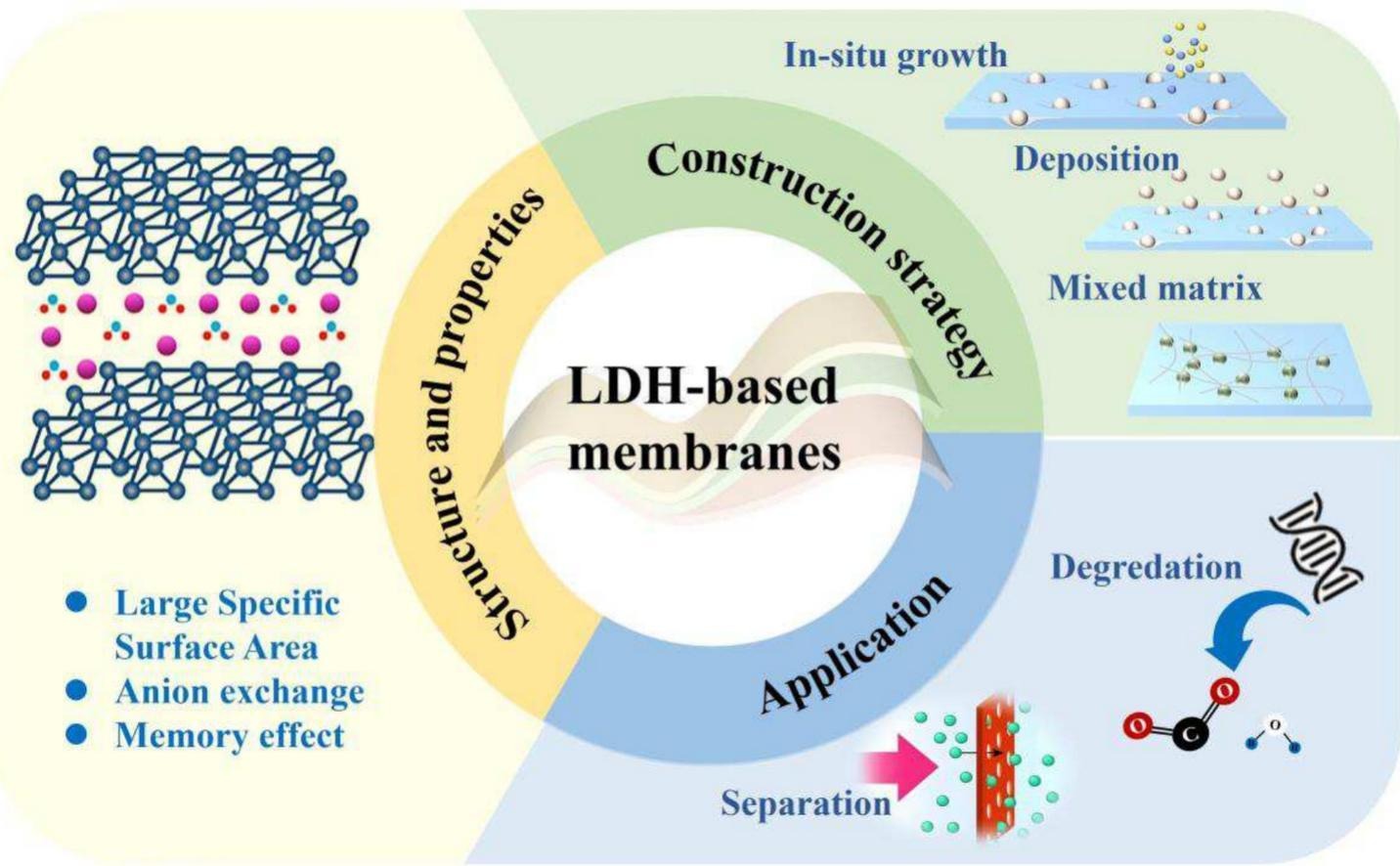

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are negatively charged molecules. LDH is a synthetic mineral material with positively charged layers, and those layers have loose anions (charged particles) sitting between them, ready to swap places with PFAS molecules the moment they come into contact. Think of it like a magnet that’s specifically tuned to grab PFAS and pull them out of the water almost instantly.

The version developed at Rice University is a copper-aluminium LDH with nitrate intercalated between its layers. The weakly-held nitrate anions are the key, they swap out rapidly with incoming PFAS, which is why the adsorption happens so fast. Under neutral pH and room temperature, lab tests showed the material could hold around 1,702 mg of PFOA (one of the most notorious PFAS compounds) per gram of material. That’s an extraordinarily high capacity.

So what is a Layered Double Hydroxide water filter, exactly? Right now, it’s mostly a lab concept — a material with massive potential that hasn’t yet made it into a consumer product. But understanding what LDH is and how it works is the first step in understanding why researchers are so excited about it.

How Fast Can an LDH Filter Remove PFAS from Tap Water?

This is where the headline numbers come in, and they are genuinely impressive. The Rice University team reported that their LDH material removed large quantities of PFAS within minutes. For context, commercial activated carbon filters, the kind in most home pitcher filters and under-sink units — can take hours to achieve comparable results. The LDH was reportedly about 100 times faster.

Tests weren’t just done in distilled lab water, either. The researchers ran the material through river water, tap water, and wastewater samples (three very different water compositions) and it performed well across all three. That’s an important detail, because a lot of experimental filtration materials fall apart the moment you throw real-world water chemistry at them.

When it comes to the fastest PFAS removal method ever demonstrated at this scale, LDH has a legitimate claim to the title. No other adsorption-based material has shown this combination of speed and capacity in peer-reviewed testing.

But here’s the catch: the “removes PFAS from tap water in minutes” claim comes from bench-scale lab tests with relatively high PFAS concentrations and controlled conditions. Real tap water is messier. Bicarbonate and carbonate ions — common in hard water — compete with PFAS for space in the LDH layers, and they reduce the material’s effectiveness. So the fastest PFAS removal method ever tested still has some real-world limitations to sort out.

Can LDH Filters Remove PFAS Better Than Reverse Osmosis?

This is the billion dollar question!

The honest answer is: in some ways, yes. In the ways that actually matter right now, not yet.

Let’s look at what we know. Reverse osmosis membranes consistently achieve over 99% removal of a wide range of PFAS — including both long-chain and short-chain variants, across varying pH levels, ionic strength, and water chemistry. It’s one of the few technologies that meets strict drinking water limits under real-world conditions, and it’s been doing so reliably for years.

LDH’s lab numbers are jaw-dropping. But can LDH filters remove PFAS better than reverse osmosis in a home or municipal setting? Not yet, for a few specific reasons:

- Hard water interference: High bicarbonate concentrations significantly reduce LDH’s adsorption efficiency. Much of the U.S. has hard water.

- Incomplete PFAS destruction: When the LDH is regenerated by heating, only about 54% of the trapped PFAS is actually broken down. The rest has to go somewhere.

- Energy intensive: Thermal regeneration requires heating to around 500°C — not exactly practical for a home filter or even most municipal plants.

- No consumer products: You can’t buy an LDH water filter anywhere right now. There are no NSF certifications, no commercial deployments, no home units.

Reverse osmosis has its own issues; it wastes roughly one gallon of water for every gallon filtered, it’s energy-intensive, and those concentrated brine streams full of PFAS need to be managed. But it works, right now, in real homes, with regulatory approval to back it up.

LDH vs. Reverse Osmosis: Side-by-Side

| Category | Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) | Reverse Osmosis (RO) |

|---|---|---|

| PFAS Removal Rate | Lab tests show extremely high adsorption capacity under ideal conditions | >99% removal across a wide range of PFAS types |

| Speed | Minutes in lab conditions | Minutes to hours depending on system design |

| Works in Hard Water? | Struggles — carbonate and bicarbonate ions interfere | Yes — handles varied water chemistry well |

| Available to Buy Now? | No — still in research phase | Yes — certified home systems from ~$450 |

| Destroys PFAS? | ~54% defluorination in lab regeneration — not complete | No — concentrates PFAS in brine waste |

| Energy Use | High — ~500°C thermal regeneration required | Moderate to high — pressure-driven membrane system |

| Regulatory Approval | None yet | NSF/ANSI 58 certified systems available |

| Long-Term Cost | Unknown — copper-based materials may be expensive | Ongoing filter and membrane replacement costs |

So the question of whether LDH filters can remove PFAS better than reverse osmosis is really two questions: on raw performance metrics in a lab, LDH is extraordinary. On practical, real-world readiness, RO wins, and it’s not particularly close, at least not today.

How Does LDH Water Filtration Actually Work Under the Hood?

There’s a little more chemistry worth understanding here, especially if you’re trying to evaluate whether LDH has staying power or is just another research flash-in-the-pan.

The copper-aluminium LDH works through two mechanisms simultaneously. First, the loose nitrate anions in the material’s interlayers swap places with incoming PFAS molecules, this is called anion exchange, and it happens very rapidly because the nitrate ions aren’t tightly bound. Second, at high PFAS concentrations, the surface of the LDH forms something like a semi-gel that physically traps additional PFAS beyond what ion exchange alone could handle. That’s partly why the capacity numbers look so much higher than theoretical limits would suggest.

After the material is saturated with PFAS, it can be regenerated by heating with calcium carbonate. The heat triggers partial breakdown of the trapped PFAS (that’s the 54% defluorination figure), and the material is prepared for another adsorption cycle. Lab tests showed it held up through at least six of these capture-and-regeneration cycles.

The fact that LDH can both capture and partially destroy PFAS sets it apart from RO, which just concentrates PFAS in brine without breaking them down. If the destruction efficiency can be pushed toward 100%, LDH could be genuinely transformative.

The interesting question is what happens when you put this into a real-world system. A continuous fixed-bed column test showed that faster water flow led to quicker breakthrough — meaning the material got saturated faster and needed regeneration sooner. That’s a solvable engineering problem, but it’s a problem that still needs solving.

Where Does LDH Water Filter Technology Stand Right Now?

The short version: early-stage, but serious. This isn’t vaporware or a speculative concept, it’s a peer-reviewed material with documented performance. But there’s a long road from lab bench to your kitchen sink.

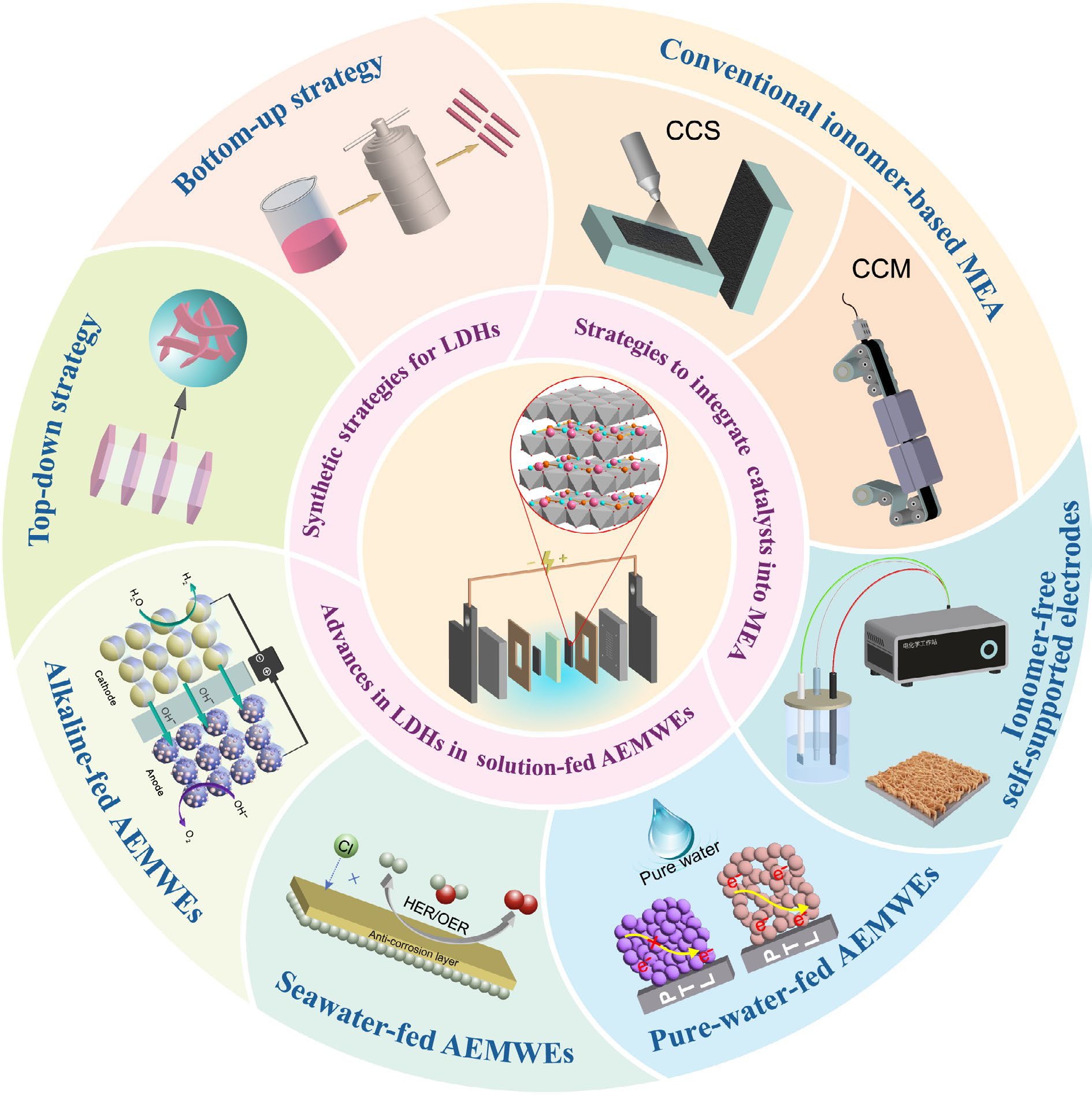

What exists today: Patents have been filed for functionalized LDHs in water treatment applications. The Department of Defense’s SERDP program is funding a proof-of-concept evaluation of LDH sorbents for groundwater cleanup. The Rice University team collaborated with international partners and received industrial funding from Saudi Aramco-KAIST. All of this signals real commercial interest, but no consumer or municipal products exist yet.

What needs to happen before you can buy one: The technology needs to clear a few major hurdles. Copper is an expensive material, and the synthesis of high-crystallinity LDH requires precise process control, both factors make scaling up tricky. The 500°C regeneration requirement needs to either come down significantly or be integrated into industrial-scale heat systems. And the incomplete PFAS destruction issue needs addressing, releasing partially-degraded PFAS back into the environment isn’t an acceptable solution.

Realistically? LDH water filter technology is unlikely to appear in certified home products before 2030 — and that’s assuming things go well. The more likely near-term scenario is LDH being used as a pre-treatment or polishing stage in municipal water systems, possibly in combination with reverse osmosis.

What Should You Actually Do About PFAS Right Now?

Here’s the practical part. If you’re worried about PFAS in your tap water — and in many areas, you probably should be — there are real options available today.

Reverse osmosis is still your best bet for comprehensive home PFAS removal. Point-of-use RO systems start around $450, are certified under NSF/ANSI 58 for PFOA and PFOS reduction, and when properly maintained, can achieve over 99% PFAS removal. Filters need replacing every 6–12 months, and membranes typically last 1–2 years. The main trade-offs are water waste (roughly 1:1 ratio) and ongoing maintenance costs.

If RO isn’t in the budget, certified activated carbon block filters (look for NSF/ANSI 53 or 58 certification) can reduce some PFAS, though they’re less comprehensive than RO and more variable depending on which PFAS compounds are present in your water.

You can find out what’s actually in your tap water through your municipal water report (required to be published annually) or by using an independent lab test if you’re on a private well.

LDH water filters represent one of the most exciting PFAS removal developments in years. But exciting and available are two very different things. For now, a certified RO system is your best tool. Keep an eye on LDH — it could change that equation significantly in the next five to ten years.

The Future: Could LDH Change Everything?

The researchers are optimistic, and it’s hard to fault them (I’m hella excited myself!). If the remaining problems around water chemistry interference, regeneration energy, and incomplete PFAS destruction can be solved, a commercial Layered Double Hydroxide water filter could offer something reverse osmosis fundamentally can’t: actual PFAS destruction, not just removal and concentration.

That’s a meaningful difference. RO creates a concentrated PFAS brine that has to be managed, treated, or disposed of — it’s essentially moving the problem rather than solving it. An LDH system that can fully defluorinate PFAS on-site would be a genuine breakthrough in the truest sense, not just a faster version of what we already have.

The most plausible path forward involves LDH entering the market as part of hybrid systems — perhaps a Layered Double Hydroxide filter stage that handles the bulk of PFAS adsorption and partial destruction, paired with RO or nanofiltration as a polishing step. Municipal water treatment plants, where energy-intensive regeneration is more economically viable, might see this technology first.

For now, the science is real, the excitement is warranted, and the timeline is uncertain. That’s kind of where every interesting technology starts.

Common Asked Questions About LDH

What is a Layered Double Hydroxide water filter?

A Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) water filter uses a synthetic mineral material with positively charged layers to attract and trap negatively charged PFAS molecules. The material exchanges loose anions in its interlayers with incoming PFAS, removing them from water very rapidly. Currently, LDH is a research-stage material — no commercial LDH water filters exist yet.

Can LDH filters remove PFAS better than reverse osmosis?

In laboratory conditions, LDH shows extraordinary PFAS adsorption capacity and speed. However, reverse osmosis consistently achieves over 99% PFAS removal in real-world conditions and is commercially available with regulatory certification. LDH filters are not yet available and have limitations in hard water and with incomplete PFAS destruction. RO wins for practical use today.

What is the fastest PFAS removal method currently available?

In lab testing, LDH-based adsorption is the fastest PFAS removal method ever demonstrated — roughly 100 times faster than activated carbon. For commercially available methods, certified reverse osmosis systems provide the most effective and consistent PFAS removal and are the recommended option for home use.

When will LDH water filters be available to buy?

Given the current state of the research, it’s unlikely that consumer LDH water filter products will be available before 2030. The technology still needs significant development around regeneration efficiency, water chemistry compatibility, and scalable manufacturing. Municipal or industrial applications may come sooner.

Does LDH destroy PFAS or just capture them?

Both, partially. The thermal regeneration process that resets LDH for reuse also breaks down (defluorinates) about 54% of the captured PFAS. The remaining 46% is not destroyed. This is actually an advantage over reverse osmosis, which doesn’t destroy PFAS at all, but full PFAS destruction remains a goal the technology hasn’t reached yet.